SecurityScience & Technology The New Revolution in Military Affairs

April 16, 2019 | by SSCI

April 16, 2019 | by SSCI

By Christian Brose

In 1898, a Polish banker and self-taught military expert named Jan Bloch published The Future of War, the culmination of his long obsession with the impact of modern technology on warfare. Bloch foresaw with stunning prescience how smokeless gunpowder, improved rifles, and other emerging technologies would overturn contemporary thinking about the character and conduct of war. (Bloch also got one major thing wrong: he thought the sheer carnage of modern combat would be so horrific that war would “become impossible.”)

What Bloch anticipated has come to be known as a “revolution in military affairs”—the emergence of technologies so disruptive that they overtake existing military concepts and capabilities and necessitate a rethinking of how, with what, and by whom war is waged. Such a revolution is unfolding today. Artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, ubiquitous sensors, advanced manufacturing, and quantum science will transform warfare as radically as the technologies that consumed Bloch. And yet the U.S. government’s thinking about how to employ these new technologies is not keeping pace with their development.

This is especially troubling because Washington has been voicing the same need for change, and failing to deliver it, ever since officials at the U.S. Department of Defense first warned of a coming “military-technical revolution,” in 1992. That purported revolution had its origins in what Soviet military planners termed “the reconnaissance-strike complex” in the 1980s, and since then, it has been called “network-centric warfare” during the 1990s, “transformation” by U.S. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld in these pages in 2002, and “the third offset strategy” by Deputy Secretary of Defense Robert Work in 2014. But the basic idea has remained the same: emerging technologies will enable new battle networks of sensors and shooters to rapidly accelerate the process of detecting, targeting, and striking threats, what the military calls the “kill chain.”

The idea of a future military revolution became discredited amid nearly two decades of war after 2001 and has been further damaged by reductions in defense spending since 2011. But along the way, the United States has also squandered hundreds of billions of dollars trying to modernize in the wrong ways. Instead of thinking systematically about buying faster, more effective kill chains that could be built now, Washington poured money into newer versions of old military platforms and prayed for technological miracles to come (which often became acquisition debacles when those miracles did not materialize). The result is that U.S. battle networks are not nearly as fast or effective as they have appeared while the United States has been fighting lesser opponents for almost three decades.

Yet if ever there were a time to get serious about the coming revolution in military affairs, it is now. There is an emerging consensus that the United States’ top defense-planning priority should be contending with great powers with advanced militaries, primarily China, and that new technologies, once intriguing but speculative, are now both real and essential to future military advantage. Senior military leaders and defense experts are also starting to agree, albeit belatedly, that when it comes to these threats, the United States is falling dangerously behind.

A U.S. Blackhawk helicopter leaving an Iraqi police base in Baghdad, February 2007 – CARLOS BARRIA / REUTERS

This reality demands more than a revolution in technology; it requires a revolution in thinking. And that thinking must focus more on how the U.S. military fights than with what it fights. The problem is not insufficient spending on defense; it is that the U.S. military is being countered by rivals with superior strategies. The United States, in other words, is playing a losing game. The question, accordingly, is not how new technologies can improve the U.S. military’s ability to do what it already does but how they can enable it to operate in new ways. If American defense officials do not answer that question, there will still be a revolution in military affairs. But it will primarily benefit others.

It is still possible for the United States to adapt and succeed, but the scale of change required is enormous. The traditional model of U.S. military power is being disrupted, the way Blockbuster’s business model was amid the rise of Amazon and Netflix. A military made up of small numbers of large, expensive, heavily manned, and hard-to-replace systems will not survive on future battlefields, where swarms of intelligent machines will deliver violence at a greater volume and higher velocity than ever before. Success will require a different kind of military, one built around large numbers of small, inexpensive, expendable, and highly autonomous systems. The United States has the money, human capital, and technology to assemble that kind of military. The question is whether it has the imagination and the resolve.

Artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies will change the way war is fought, but they will not change its nature. Whether it involves longbows or source code, war will always be violent, politically motivated, and composed of the same three elemental functions that new recruits learn in basic training: move, shoot, and communicate.

Movement in warfare entails hiding and seeking (attackers try to evade detection; defenders try to detect them) and penetrating and repelling (attackers try to enter opponents’ space; defenders try to deny them access). But in a world that is becoming one giant sensor, hiding and penetrating—never easy in warfare—will be far more difficult, if not impossible. The amount of data generated by networked devices, the so-called Internet of Things, is on pace to triple between 2016 and 2021. More significant, the proliferation of low-cost, commercial sensors that can detect more things more clearly over greater distances is already providing more real-time global surveillance than has existed at any time in history. This is especially true in space. In the past, the high costs of launching satellites required them to be large, expensive, and designed to orbit for decades. But as access to space gets cheaper, satellites are becoming more like mobile phones—mass-produced devices that are used for a few years and then replaced. Commercial space companies are already fielding hundreds of small, cheap satellites. Soon, there will be thousands of such satellites, providing an unblinking eye over the entire world. Stealth technology is living on borrowed time.

On top of all of that, quantum sensors—which use the bizarre properties of subatomic particles, such as their ability to be in two different places at once—will eventually be able detect disruptions in the environment, such as the displacement of air around aircraft or water around submarines. Quantum sensors will likely be the first usable application of quantum science, and this technology is still many years off. But once quantum sensors are fielded, there will be nowhere to hide.

The future of movement will also be characterized by a return of mass to the battlefield, after many decades in which the trend was moving in the opposite direction—toward an emphasis on quality over quantity—as technology is enabling more systems to get in motion and stay in motion in more places. Ubiquitous sensors will generate exponentially greater quantities of data, which in turn will drive both the development and the deployment of artificial intelligence. As machines become more autonomous, militaries will be able to field more of them in smaller sizes and at lower costs. New developments in power generation and storage and in hypersonic propulsion will allow these smaller systems to travel farther and faster than ever. Where once there was one destroyer, for example, the near future could see dozens of autonomous vessels that are similar to missile barges, ready to strike as targets emerge.

Technology will also transform how those systems remain in motion. Logistics—the ability to supply forces with food, fuel, and replacements—has traditionally been the limiting factor in war. But autonomous militaries will need less fuel and no food. Advanced manufacturing methods, such as 3-D printing, will reduce the need for vast, risky, and expensive military logistics networks by enabling the production of complicated goods at the point of demand quickly, cheaply, and easily.

In an even more profound change, space will emerge as its own domain of maneuver warfare. So far, the near impossibility of refueling spacecraft has largely limited them to orbiting the earth. But as it becomes feasible to not just refuel spacecraft midflight but also build and service satellites in space, process data in orbit, and capture resources and energy in space for use in space (for example, by using vast solar arrays or mining asteroids), space operations will become less dependent on earth. Spacecraft will be able to maneuver and fight, and the first orbital weapons could enter the battlefield. The technology to do much of this exists already.

Technology will also radically alter how militaries shoot, both literally and figuratively. Cyberattacks, communication jamming, electronic warfare, and other attacks on a system’s software will become as important as those that target a system’s hardware, if not more so. The rate of fire, or how fast weapons can shoot, will accelerate rapidly thanks to new technologies such as lasers, high-powered microwaves, and other directed-energy weapons. But what will really increase the rate of fire are intelligent systems that will radically reduce the time between when targets can be identified and when they can be attacked. A harbinger of this much nastier future battlefield has played out in Ukraine since 2014, where Russia has shortened to mere minutes the time between when their spotter drones first detect Ukrainian forces and when their precision rocket artillery wipes those forces off the map.

The militaries of the future will also be able to shoot farther than those of today. Eventually, hypersonic munitions (weapons that travel at more than five times the speed of sound) and space-based weapons will be able to strike targets anywhere in the world nearly instantly. Militaries will be able to attack domains once assumed to be sanctuaries, such as space and logistics networks. There will be no rear areas or safe havens anymore. Swarms of autonomous systems will not only be able to find targets everywhere; they will also be able to shoot them accurately. The ability to have both quantity and quality in military systems will have devastating effects, especially as technology makes lethal payloads smaller.

The militaries that embrace and adapt to these technologies will dominate those that do not.

Finally, the way militaries communicate will change drastically. Traditional communications networks—hub-and-spoke structures with vulnerable single points of failure—will not survive. Instead, technology will push vital communications functions to the edge of the network. Every autonomous system will be able to process and make sense of the information it gathers on its own, without relying on a command hub. This will enable the creation of radically distributed networks that are resilient and reconfigurable.

Technology is also inverting the current paradigm of command and control. Today, even a supposedly unmanned system requires dozens of people to operate it remotely, maintain it, and process the data it collects. But as systems become more autonomous, one person will be able to operate larger numbers of them single-handedly. The opening ceremonies of the 2018 Winter Olympics, in South Korea, offered a preview of this technology when 1,218 autonomous drones equipped with lights collaborated to form intricate pictures in the night sky over Pyeongchang. Now imagine similar autonomous systems being used, for example, to overwhelm an aircraft carrier and render it inoperable.

Further afield, other technologies will change military communications. Information networks based on 5G technology will be capable of moving vastly larger amounts of data at significantly faster speeds. Similarly, the same quantum science that will improve military sensors will transform communications and computing. Quantum computing—the ability to use the abnormal properties of subatomic particles to exponentially increase processing power—will make possible encryption methods that could be unbreakable, as well as give militaries the power to process volumes of data and solve classes of problems that exceed the capacity of classical computers. More incredible still, so-called brain-computer interface technology is already enabling human beings to control complicated systems, such as robotic prosthetics and even unmanned aircraft, with their neural signals. Put simply, it is becoming possible for a human operator to control multiple drones simply by thinking of what they want those systems to do.

Put together, all these technologies will displace decades-old, even centuries-old, assumptions about how militaries operate. The militaries that embrace and adapt to these technologies will dominate those that do not. In that regard, the U.S. military is in big trouble.

Drones form images over the night sky at the Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang, South Korea, February 2018 – ERIC GAILLARD / REUTERS

Since the end of the Cold War, the United States’ approach to projecting military force against regional powers has rested on a series of assumptions about how conflicts will unfold. The U.S. military assumes that its forces will be able to move unimpeded into forward positions and that it will be able to commence hostilities at a time of its choosing. It assumes that its forces will operate in permissive environments—that adversaries will be unable to contest its freedom of movement in any domain. It assumes that any quantitative advantage that an adversary may possess will be overcome by its own superior ability to evade detection, penetrate enemy defenses, and strike targets. And it assumes that U.S. forces will suffer few losses in combat.

These assumptions have led to a force built around relatively small numbers of large, expensive, and hard-to-replace systems that are optimized for moving undetected close to their targets, shooting a limited number of times but with extreme precision, and communicating with impunity. Think stealth aircraft flying right into downtown Belgrade or Baghdad. What’s more, systems such as these depend on communications, logistics, and satellite networks that are almost entirely defenseless, because they were designed under the premise that no adversary would ever be able to attack them.

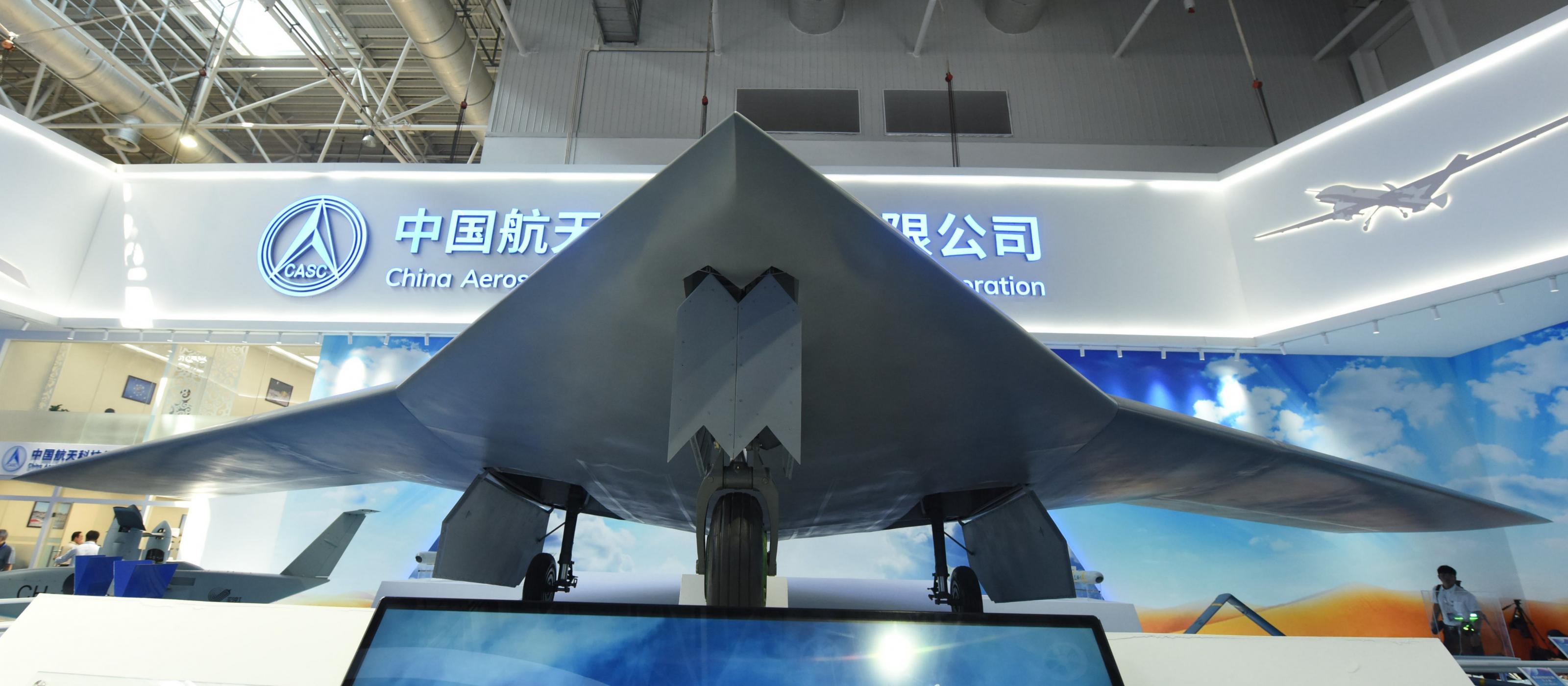

This military enterprise and its underlying suppositions are being called into question. For the past two decades, while the United States has focused on fighting wars in the Middle East, its competitors—especially China, but also Russia—have been dissecting its way of war and developing so-called anti-access/area-denial (or A2/AD) capabilities to detect U.S. systems in every domain and overwhelm them with large salvos of precision fire. Put simply, U.S. rivals are fielding large quantities of multimillion-dollar weapons to destroy the United States’ multibillion-dollar military systems.

China has also begun work on megaprojects designed to position it as the world leader in artificial intelligence and other advanced technologies. This undertaking is not exclusively military in its focus, but every one of these advanced-technology megaprojects has military applications and benefits the People’s Liberation Army under the doctrine of “military-civil fusion.” Whereas the U.S. military still largely treats its data like engine exhaust—a useless byproduct—China is moving with authoritarian zeal to stockpile its data like oil, so that it can power the autonomous and intelligent military systems it sees as critical to dominance in future warfare.

The United States’ position, already dire, is rapidly deteriorating. As a 2017 report from the RAND Corporation concluded, “U.S. forces could, under plausible assumptions, lose the next war they are called upon to fight.” That same year, General Joseph Dunford, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, sounded the alarm in stark terms: “In just a few years, if we do not change the trajectory, we will lose our qualitative and quantitative competitive advantage.”

The greatest danger for the United States is the erosion of conventional deterrence. If leaders in Beijing or Moscow think that they might win a war against the United States, they will run greater risks and press their advantage. They will take actions that steadily undermine the United States’ commitments to its allies by casting doubt on whether Washington would really send its military to defend the Baltics, the Philippines, Taiwan, or even Japan or South Korea. They will try to get their way through any means necessary, from coercive diplomacy and economic extortion to meddling in the domestic affairs of other countries. And they will steadily harden their spheres of influence, turning them into areas ever more hospitable to authoritarian ideology, surveillance states, and crony capitalism. In other words, they will try, as the military strategist Sun-tzu recommended, to “win without fighting.”

The United States is still betting that by incrementally upgrading its traditional military systems, it can remain dominant for decades to come. This approach might buy time, but it will not allow the U.S. military to regain superiority over its rivals. Doubling down on the status quo is exactly what Washington’s competitors want it to do: if the U.S. government spends more money in the same ways and on the same things, it will simply build more targets for its competitors while bankrupting itself.

Washington must banish the idea that the goal of military modernization is simply to replace the military platforms it has relied on for decades.

It’s time to think differently, and U.S. defense planners should start by adopting more realistic assumptions. They should assume that U.S. forces will fight in highly contested environments against technologically advanced opponents, that they will be unlikely to avoid detection in any domain, and that they will lose large numbers of military systems in combat. Washington must also banish the idea that the goal of military modernization is simply to replace the military platforms it has relied on for decades, such as fighter jets and aircraft carriers, with better versions of the same things. It must focus instead on how to buy systems that can be combined into networks or kill chains to achieve particular military outcomes, such as air superiority or control of the seas. Finally, the old belief that software merely supports hardware must be inverted: future militaries will be distinguished by the quality of their software, especially their artificial intelligence.

What would a military built on those assumptions look like? First, it would have large quantities of smaller systems: swarms of intelligent machines that distribute sensing, movement, shooting, and communications away from vulnerable single points of failure and out to the edges of vast, dispersed networks. Such an approach would impose costs on competitors, as they would no longer be able to concentrate on a few big targets and would instead need to target many things over larger spaces.

Second, those systems would be cheap and expendable, which would make it easier to endure large-scale losses in combat. If it takes the United States’ competitors more time and money to destroy U.S. systems than it does for the United States to replace those systems, the United States will win over time.

Finally, these systems would be unmanned and autonomous to the extent that is ethically acceptable. Keeping humans alive, safe, and comfortable inside machines is expensive—and no one wants to pay the ultimate price of lost human life. Autonomous systems are cheaper to field and cheaper to lose. They can also free humans from doing work that machines can do better, such as processing raw sensor data or allocating tasks among military systems. Liberating people from such work will prove crucial for managing the volume and velocity of the modern battlefield, but also for enabling people to focus more energy on making moral decisions about the intended outcomes of warfare. In this way, greater autonomy can not only enhance military effectiveness; it can also allow more humans to pay more attention to the ethics of war than ever before.

Building this kind of military is not only desirable; it is becoming technologically feasible. The U.S. military already has a number of programs in development aimed at just such a future force, from low-cost autonomous aircraft to unmanned underwater vehicles that could compose an artificially intelligent network of systems that is more resilient and capable than traditional military programs. For now, none of these systems is as capable as legacy programs such as the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter or the Virginia-class submarine, but they also carry a small fraction of the costs. The goal should be not to buy more individual platforms but to buy faster kill chains. The money currently invested in one legacy system could buy dozens of autonomous systems that add up to a superior capability.

An X-47B pilot-less drone is launched off an aircraft carrier off the coast of Virginia, May 2013 – JASON REED / REUTERS

The purpose of this kind of military—one that relies heavily on swarms of thousands of small, low-cost, autonomous systems that can dominate all domains—would not be to provoke war. It would be to deter it, by demonstrating that the United States can destroy any force its competitors put onto the battlefield in any domain, replenish its combat losses faster and cheaper than they can, and sustain a fight until it wins by attrition. The purpose of preparing for war will remain to never have to fight one.

Military modernization of this kind will not happen all at once. Autonomous systems may rely on legacy systems, including aircraft carriers, for some time to come. But even this will require significant changes to how traditional systems are configured and operated. Some leaders in Congress and the executive branch want to embrace these changes, which is encouraging. But if this transition fails—and the odds of that are unsettlingly high—it will likely fail for reasons other than the ethical opposition that is the focus of current debates, which seeks to “ban killer robots” or ensure that commercial technology companies do nothing to benefit the U.S. military.

There are serious ethical concerns. The military use of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence requires sober debate, but that debate should not be reduced to a binary decision between human and machine control. If framed clearly, many of the technological and moral questions facing policymakers can be answered within the confines of existing law and practice. For example, the legal concept of “areas of active hostilities,” in which the threshold for using violence is reduced in limited geographic areas, could provide useful answers to the moral dilemmas posed by lethal autonomous weapons.

The real challenge facing policymakers is how to imbue intelligent machines with human intent, and that is not a new problem. And although this new technology will present ethical dilemmas, it will also help resolve them. Autonomous systems will enable humans to spend less time on menial problems and more time on moral ones. Intelligent machines will likely become more capable of differentiating between, say, tanks and other vehicles, than a scared 19-year-old is. Americans will naturally be apprehensive about trusting machines to perform what have traditionally been human tasks. But the greater danger right now is that Americans will move too slowly and not be trusting enough, especially as China and Russia are proceeding with fewer ethical concerns than the United States. Unless Washington is willing to unilaterally cede that advantage to its rivals, it cannot allow itself to become paralyzed by the wrong questions.

If the United States fails to take advantage of the new revolution in military affairs, it will be less for ethical reasons and more as a result of the risk-averse, status quo mentality that pervades its domestic institutions. Former U.S. Secretary of Defense Robert Gates explained why in his memoir, Duty:

The military departments develop their budgets on a five-year basis, and most procurement programs take many years—if not decades—from decision to delivery. As a result, budgets and programs are locked in for years at a time, and all of the bureaucratic wiles of each military department are dedicated to keeping those programs intact and funded. They are joined in those efforts by the companies that build the equipment, the Washington lobbyists that those companies hire, and the members of Congress in whose states or districts those factories are located. Any threats to those long-term programs are not welcome.

This is what Senator John McCain, a Republican from Arizona, once called “the military-industrial-congressional complex,” and its entire livelihood depends on developing, producing, acquiring, operating, and maintaining traditional defense systems in traditional ways.

Some in this complex may seem welcoming to advanced technologies now because they still don’t view them as threats. For a transitional period, advanced technologies will indeed support, rather than replace, traditional systems. But as the backers of traditional systems come to see intelligent machines as substitutes for those systems, they will resist change. Bureaucrats who derive power from their mastery of the current system are loath to alter it. Military pilots and ship drivers are no more eager to lose their jobs to intelligent machines than factory workers are. Defense companies that make billions selling traditional systems are as welcoming of disruptions to their business model as the taxi cab industry has been of Uber and Lyft. And as all this resistance inevitably translates into disgruntled constituents, members of Congress will have enormous incentives to stymie change.

Overcoming these obstacles will require leadership at the highest levels of government to set clear priorities, drive change in resistant institutions, remake their incentive structures, and recast their cultures. That may be too much to expect, especially amid Washington’s current political turmoil. There are many capable, well-intentioned leaders in the Pentagon, Congress, and the private sector who know that the U.S. defense program needs to change. But too often, the leaders who understand the problem the best lack the power to address it at the scale required, while those with the most power either don’t understand the problem or don’t know what to do about it.

This points to a broader problem: a fundamental lack of imagination. U.S. leaders simply do not believe that the United States could be displaced as the world’s preeminent military power, not in the distant future but very soon. They do not have the vision or the sense of urgency needed to alter the status quo. If that attitude prevails, change could come not from a concerted plan but as a result of a catastrophic failure, such as an American defeat in a major war. By then, however, it will probably be too late to alter course. The revolution in military affairs will have been not a trend that the United States used to deter war and buttress peace but a cause of the United States’ destruction.

With Insights from Integration Exercise, SubT Challenge Competitors Prepare...

With Insights from Integration Exercise, SubT Challenge Competitors Prepare...